A Primer on Hedging Oil

The Power and Natural Resources (PNR) sector is a highly cyclical industry dependent on oil prices. Companies in the PNR sector, such as ExxonMobil and PetroChina, are price-takers and have no strong influence over commodity prices alone. At the same time, erratic fluctuations in such prices can directly impact revenue, earnings, company valuation, and therefore, shares trading price. Given that GCI is a value investment fund, questions arise as to how PNR companies protect themselves against the uncertain economic risks. This article will serve as an introduction to implications of oil price fluctuation and company hedging techniques.

Inelasticity of Quantity Supplied and Demanded

**Change in demand/supply refers to the shift of the respective curves, whereas quantity demanded/supplied refers to movement along the curve.

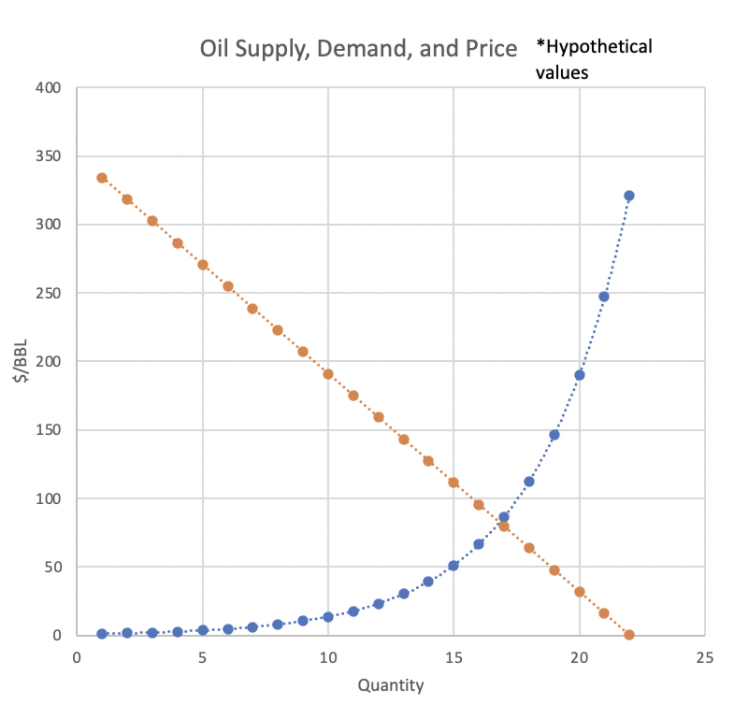

Like the prices of nearly all products, oil price can roughly be estimated by the intersection of the supply and demand of the market. Increase/decrease in supply/demand will shift curves to establish a new price and quantity, but at a constant level, quantity supplied/demanded is characterized by short-term inelasticity. I will describe the important factors and players that influence oil’s supply and demand below.

Supply

Supply comes from two main segments: OPEC and non-OPEC (think of non-OPEC as conventional oil companies). OPEC functions as a cartel that accounts for 40% of the world’s oil output. Production is generally set at a predetermined level to ensure stability.

Conventional companies, on the other hand, have huge fixed expenses to account and therefore produce as long as the total cost per barrel (bbl) does not exceed the market price per bbl (ideally).

Inelasticity in supply comes from the predetermined level of production as well as highly specialized fixed costs. PPE in companies is generally high and specialized for oil production. As price changes, the cost of shutting down an oil field to curb supply is high, and the cost of building new infrastructure to increase supply is also high.

Demand

Oil consumption is generally attributable to the logistics and travel industry, as well as individual households.

The major players in the logistics/travel industry are cargo ship companies and airlines. These companies are unlikely to cancel their flights/shipments due to changes in oil price (they might price the customer higher, though, but they will still consume that oil).

Similarly, households are unlikely to stop driving their cars because of higher oil prices. Households need natural gas (a byproduct of oil drilling) to heat their homes and oil to fuel their cars for daily transportation.

As a result of these factors, inelasticity in demand comes from the relatively stable consumption of oil.

So, what does this mean?

So theoretically, since supply and demand are relatively stable, the market price of oil should stay stable as well, right? In reality, this isn’t usually the case.

If the price changes greatly for no apparent reason, there should be roughly the same level of consumption and supply. You can infer that there is stability and room in the market for prices to eventually self-correct, unless there is a change in overall demand or supply.

The overall trend for demand is generally increasing. Developing economies need oil to build their factories and ship their products, while developed economies need a steady stream of commodities to fuel their existing networks of infrastructure. A driver that decreases demand is increasingly energy efficient machines.

Shifts in supply fluctuate quite drastically. OPEC members regularly go above the predetermined level of production at an unpredictable level due to the lack of retribution. At the same time, non-OPEC companies located in oil-rich countries, e.g. Russia, might be driven to increase/decrease supply due to a variety of geopolitical reasons. As a result, oil prices do fluctuate quite drastically in an unpredictable pattern (excluding seasonal patterns).

When oil prices are high, the oil industry has higher margins and earnings. Companies tend to devote a significant portion of this earning back into capital expenditure projects, such as acquiring new oil fields. However, high oil prices are busts for other sectors of the economy, as cost of fuel or cost of production increases, driving to lower margins.

Vice-versa for when oil prices are low. PNR companies struggle quite a bit when oil prices are low. The other sectors of the economy tend to perform well when oil price decreases.

Risk Management Techniques

So, how do companies protect themselves against drops in oil prices? Almost all oil companies “hedge” their products. This allows companies to “lock-in” a certain price for their oil and therefore protects them against a market decline. In practice, companies use derivative instruments to “bet” in the other direction, similar to shorting a stock, so that when prices do drop, they profit from some hedging gains.

Hedging is a complicated practice with a variety of techniques that take experience and an in-depth understanding of oil pricing. For the sake of simplicity, I will talk about two of the techniques: futures and the “costless” collar using intuitive examples.

Futures

Oil futures trade on the New York Mercantile Exchange (NYMEX), and it is the right and obligation to purchase a number of bbls of oil at a set price. Each underlying contract is for 1000 bbls of oil, and the face value is in terms of dollars per bbl. Although futures are contracts to buy actual barrels of oil, little of the contracts result in actual delivery. There is often a cash buyout option with each contract.

If an oil company wants to hedge their November oil production, they would buy/sell a mix of November and December futures preemptively, because November and December futures expire on 10/20 and 11/20, respectively. Since the expiration dates are in the middle of the months, a mixture of the two months is needed to properly hedge it.

At the time of writing, oil futures hover around $40.87. So, for this example, let’s assume the strike price is $40.87.

Come November, there are two possibilities: the trading oil price could be higher or it could be lower than the strike price.

In the scenario where the oil price is higher than the strike price, say $50, you would receive approximately $50 per bbl, minus any transportation or extraction fees. However, from that, we must subtract $9.23 per bbl to account for the spread (|$50-$40.87|). This $9.23 is a hedging loss for having traded futures. Since hedging is against a drop in oil price, in this case, oil price actually increased and the risk was not realized.

In the second scenario where the oil price is lower than the strike price, say $30, you would receive approximately $30 per bbl. The spread in this case is $10.87 (|$30-$40.87|), meaning there is a $10.87 hedging gain per bbl. This is a scenario where hedging pays off, and the firm is able to benefit from hedging. However, in the bigger picture, the company is likely to suffer from lower operating revenue.

Futures is one of the ways companies use to manage their risks. However, a lot of companies think of it as a “zero-sum” game of guessing prices, and it has gotten a reputation among some oil companies as “gambling”. As a result, companies use the following method more frequently due to its higher versatility.

The “Costless” Collar

The “costless” collar is the combination of two options at two ends of a reasonable price range, referred to as a floor and a ceiling. The company would buy a put option (floor) and sell a call option (ceiling). It uses the premium gained from selling the call option to offset the premium of buying the put option, thereby giving the rise of the term “costless”.

The key to a well-executed “costless” collar is to align the premiums, so they cancel off each other. This includes timing the market and volume during trading hours, or purchasing these positions in advance to the volatile trading periods (2-5 weeks leading up to expiration). If the premium gained is lower than the premium bought, the company has to pay the out of pocket difference, and the benefit of hedging against both sides diminishes.

To illustrate this example, let’s assume a company buys a $30 put option with a $2 premium and sells a $50 call option also with a $2 premium. The company has taken a $30/$50 costless collar, while the premiums cancel each other out.

There are three scenarios that could happen: the price oil goes below $30, above $50, or in between $30 and $50.

If the price is $25, which is below $30, the company benefits from a $5 per bbl hedging gain. The company benefits from hedging.

If the price is $57, which is above $50, the company suffers a $7 per bbl hedging loss. However, again, a hedging loss essentially suggests oil price went up and that the risk of oil price dropping is not realized.

If the price falls between $30 and $50, there is no hedging loss or gain. For example, if the average settlement price is $40, the net price for your production will be $40 per bbl. This range of break-even is unique to taking on both of the option positions, and many companies chose to do the “costless” collar because of this range.

Final words:

The biggest takeaway from this article is perhaps not the minute details of hedging, but rather that oil companies are incredibly price-sensitive and, therefore, risk-averse. As demonstrated above, regardless of hedging methods, companies expose themselves to potential hedging losses. In the grand picture however, these losses are like insurance payments – in case of a rainy day. When oil price does drop, hedging gains will help offset the lower margins from lower oil price.

Historically, companies have overly relied on hedging without examining the macroeconomic trends of developing economies and the subsequent growth in oil price. Companies need to think carefully about the risk of selling call options in an environment where there is sustainable oil price growth. Especially in the considerably less liquid derivative market with higher spreads, the effects of an inaccurate price projection are often multiplied by a large factor. Having a hedge is not a reason to stop analyzing the bigger market trends for price fluctuations. To consistently generate profit and cash flow, companies should combine various hedging methods while paying a close, in-depth attention on greater economic trends.